For decades, we’ve sorted human bodies into three neat biotypology (study of human types based on morphological, physiological, and psychological characteristics) categories: the lean ectomorph, the muscular mesomorph, and the softer endomorph (Martinez-Mirelles et al., 2025). In parallel, psychology has explored the link between our physical constitution and our temperament, a concept known as somatopsychology. Ancient Greek physicians like Hippocrates and Galen proposed that body fluids (“humors”) dictated personality, from the melancholic to the sanguine. This idea was revived in the 20th century by psychologist William Sheldon (Ulsperger, 2014), who directly mapped his three “somatotypes” to three temperament types: the cerebrotonic ectomorph (inhibited, thoughtful, introverted), the somatotonic mesomorph (assertive, energetic, dominant), and the viscerotonic endomorph (relaxed, sociable, comfort-seeking).

While Sheldon’s theories and methodology have been criticized by modern science, they tapped into a persistent human intuition: that the body and mind are inextricably linked, and that our biology might influence our psychological predispositions. But what if the key to understanding this mind-body connection isn’t just in our genes or our thoughts, but in the trillions of microscopic tenants living in our gut?

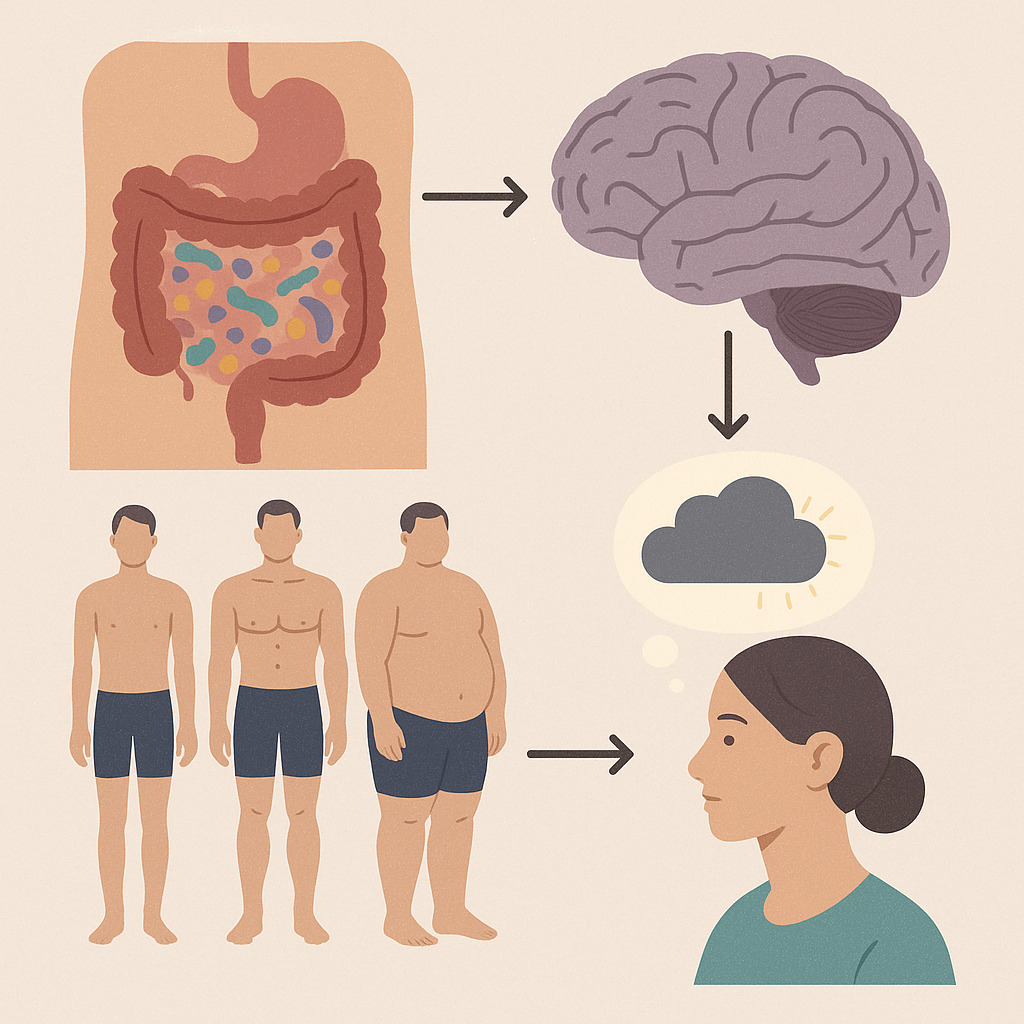

Emerging research is revealing a profound dialogue between our gut microbiome, our body’s fundamental structure, and our brain (Kim & Shim, 2023). This isn’t just about weight; it’s about how the very bacteria we host might influence our physiology, our cravings, and even our mental state, creating a feedback loop that science is just beginning to decode.

The Three Constitutional Types: A Quick Primer

While modern science avoids overly rigid classifications, the concepts of ectomorph, mesomorph, and endomorph, remain a useful framework for discussing innate physiological tendencies.

- Ectomorph: Characterized by a lean, slender frame, fast metabolism, and difficulty gaining weight or muscle mass.

- Mesomorph: Naturally athletic and muscular, with a body that gains and loses weight easily, often with a rectangular or hourglass shape.

- Endomorph: Tends to have a softer, rounder body, a slower metabolism, and a greater propensity to store fat, often finding it challenging to lose weight.

As above-mentioned these were linked to temperamental types (cerebrotonic, somatotonic, viscerotonic). However, the core physical distinctions persist in fitness and wellness conversations. The new question is: could our gut microbiome be a biological factor influencing these tendencies?

The Garden in Your Gut: Meet the Key Players

Your gut microbiome is a complex ecosystem, but research has started to identify specific types of bacteria that play outsized roles in metabolism and body weight (Rinninella et al., 2019). Two of the most studied genera are:

- Bacteroidetes: Often dubbed the “lean bacteria.” Higher ratios of Bacteroidetes are generally associated with leaner body types. These microbes are efficient at breaking down dietary fiber and complex plant polysaccharides into short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) like butyrate. Butyrate is crucial—it nourishes the gut lining, reduces inflammation, and improves insulin sensitivity, helping the body use energy more efficiently rather than storing it as fat.

- Firmicutes: Often labeled the “obese bacteria.” A higher Firmicutes-to-Bacteroidetes ratio is frequently observed in individuals with obesity. Firmicutes are exceptionally proficient at extracting calories from food. They break down otherwise indigestible fibers, allowing for more energy (calories) to be absorbed. While this was a survival advantage for our ancestors, in a modern world of caloric abundance, it can contribute to weight gain.

- Prevotella vs. Ruminococcus: Beyond these two, other bacteria like Prevotella (associated with plant-based diets and improved glucose metabolism) and Ruminococcus (linked to higher BMI and energy extraction) also play significant roles in shaping our metabolic health.

The Microbiome-Body Type Correlation: A Hypothetical Map

While research is ongoing and individual variation is immense, we can speculate on fascinating correlations between gut bacteria and constitutional types. Think of this not as a deterministic fate, but as a prevailing microbial landscape that influences the body’s tendencies.

- The Ectomorph’s Gut: Might be dominated by a diverse array of Bacteroidetes and other microbes that are less efficient at energy extraction. Food might pass through with fewer calories absorbed, supporting a naturally leaner frame. Their gut may produce SCFAs that promote a healthy metabolism but not excessive energy storage. This could be the microbial underpinning of the “fast metabolism.”

- The Endomorph’s Gut: Could show a higher Firmicutes-to-Bacteroidetes ratio. This “thrifty” microbiome excels at harvesting every last calorie, making energy storage efficient. Combined with other factors, this can create a physiological reality where the body is predisposed to holding onto weight. It’s not a lack of willpower; it’s a highly efficient internal calorie-saving program run by microbes.

- The Mesomorph’s Gut: Likely possesses a balanced and adaptable microbiome. This ecosystem may be highly responsive to diet and exercise, efficiently using energy for muscle repair and function (anabolic processes) rather than primarily for storage. The microbial community might support low inflammation and optimal nutrient partitioning—directing fuel to muscle rather than fat cells.

It’s important to remember that diet is a primary driver of microbiome composition. An ectomorph eating a standard Western diet may develop a “Firmicute-heavy” profile, and an endomorph on a high-fiber, diverse diet can significantly shift their microbial balance toward a healthier state. Your body type may influence your starting point, but you are the head gardener.

Neuroscience and Psychonutrition: Rewiring the Loop from Brain to Gut

This is where the field of psychonutrition or neuronutrition comes in. It’s the study of how nutrients affect the brain and, consequently, our mood, cognition, and behavior (Achour et al., 2022). Neuroscience provides the tools to understand this gut-brain axis (Mayer et al., 2014).

The vagus nerve is the superhighway of communication between the gut and the brain. Gut microbes produce neurotransmitters (like GABA, serotonin, and dopamine) and other metabolites (like SCFAs) that send signals up this nerve to the brain.

- Cravings and Appetite Control: Your microbes influence what you eat to feed themselves. Sugar-loving bacteria can hijack the brain’s reward pathways (involving dopamine), prompting cravings for the very foods that help them thrive. A diet high in processed foods cultivates a microbiome that demands more processed foods (Kim et al., 2023).

- Stress and the Gut: Neuroscience shows that chronic stress (high cortisol) can increase gut permeability (“leaky gut”), triggering inflammation that affects the brain and can disrupt healthy microbial balance. This creates a vicious cycle: stress alters the microbiome, and a dysbiotic microbiome can exacerbate anxiety and stress reactivity (Madison & Baiely, 2024).

- Intervention through Nutrition: The goal of psychonutrition is to use food to break this cycle. Consuming:

- Prebiotics (fiber that feeds good bacteria): onions, garlic, asparagus, bananas. Probiotics (live beneficial bacteria): yogurt, kefir, kimchi, sauerkraut (Wijesekara & Xu, 2025).

- Psychobiotics—probiotics targeted to mental health—hold promise for improving mental well-being via the gut-brain axis by modulating neurotransmitters, inflammation, and neural signaling (Sharma et al., 2021).

- Polyphenols (plant compounds that support microbes): berries, green tea, dark chocolate.

…can actively shift the microbial population. This change reduces inflammation, improves gut barrier function, and sends healthier signals via the vagus nerve, positively influencing mood, cravings, and metabolic health.

The Takeaway: You Are the Ecosystem Manager

The old dichotomy of nature vs. nurture is obsolete. We are not just our inherited body type or our genes. We are a superorganism, a collaboration between human cells and microbial ones. Your constitutional type may be your hardware, but your microbiome is a key piece of software that you can reprogram.

By understanding the powerful triad of your gut, your body’s tendencies, and your brain, you can move beyond simplistic body stereotypes. You can use targeted nutrition not just to feed yourself, but to cultivate a microbial garden that supports a healthy weight, a resilient metabolism, and a calmer, clearer mind. The science is clear: the path to well-being is paved not just with good food, but with good bacteria.

The content provided is for informational purposes only and does not constitute medical advice. Always consult with a healthcare professional before making any significant changes to your diet or lifestyle.

✨ At Daisy Clinic, we believe in healing the mind-body connection. Our neuropsychotherapists integrate the principles of psychonutrition into therapy to help clients understand the powerful link between food, brain, and emotions. Using neuroscience insights, we explore how certain foods influence mood, cravings, and resilience—while building mindful, healthier patterns in everyday life.

“Every bite we take is not just fuel, it is information for the brain. By understanding how nutrients shape neurotransmitters like serotonin and dopamine, clients gain the power to shift their mood, manage cravings, and build resilience.” — Dr. Ralu Maxim, Neuroscientist & Neuropsychotherapist

The neuroscience in simple terms:

When you eat sugary or highly processed foods, your gut microbes send signals through the vagus nerve to your brain, activating dopamine pathways that create powerful cravings. Over time, this can reinforce emotional eating cycles. On the other hand, nutrients from fiber-rich foods, fermented foods, and plant compounds help release serotonin and GABA—neurotransmitters that calm the nervous system and stabilize mood.

A simple exercise for practice:

- Pause before eating. Take three slow breaths to activate your parasympathetic “rest and digest” system.

- Check your craving. Ask yourself: Am I feeding my body’s hunger or my brain’s stress?

- Reframe the choice. If it’s emotional hunger, note the feeling in a journal before eating. If it’s physical hunger, choose a food that will feed your brain—something with fiber, protein, or probiotics.

At Daisy Clinic, our goal is to help you strengthen mental resilience and create a more conscious, compassionate relationship with food. If you’re ready to explore this journey, we invite you to begin with us today.